Disclosure: This content may contain affiliate links. Read my disclosure policy.

Introduction: The Catskill Forests

The Catskill forests are dominated by maple, oak, beech and birch, but conifer species are a significant player in the landscape. According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, “The three major forest types in the eastern Catskills, from the highest elevations to the lowest, include spruce-fir forest, northern hardwoods forest, and oak-hickory forest.”

Our conifer-dominated forests are largely confined to mountaintops, riparian corridors and stream bottoms. Spend any time in the Catskills and you’ll see how special our hemlock groves are — and how unique their micro-environment is.

Now they’re under threat…

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Webinar | April 3, 2020

This webinar was presented by Charlotte Malmborg of the NYS Hemlock Initiative and sponsored by the Adirondack Park Invasive Plant Program and Adirondack Mountain Club.

Notes

Following are the notes I took while watching the video webinar above…

Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga Canadensis)

Hemlocks are the third most common tree in New York State, and they are a foundational species. They create the forest ecosystem they live in.

The species is important for four main reasons…

- Hemlock fills a niche by growing where a lot of other trees can’t: on steep slopes and in shady areas.

- Hemlock supports an entire food web: deer and porcupine in the winter, as well as 400 forest species year-round (birds, mammals, arthropods).

- Hemlock provides unique ecosystem services: it helps keep freshwater streams cold and clean, and provides direct shade from dense canopies.

- Hemlock creates unique habitats: soil and water chemistry conditions, and tannic properties, acidic soil, improves overall biodiversity, keeps forest stable and diverse (e.g. brook trout depend on hemlock habitat).

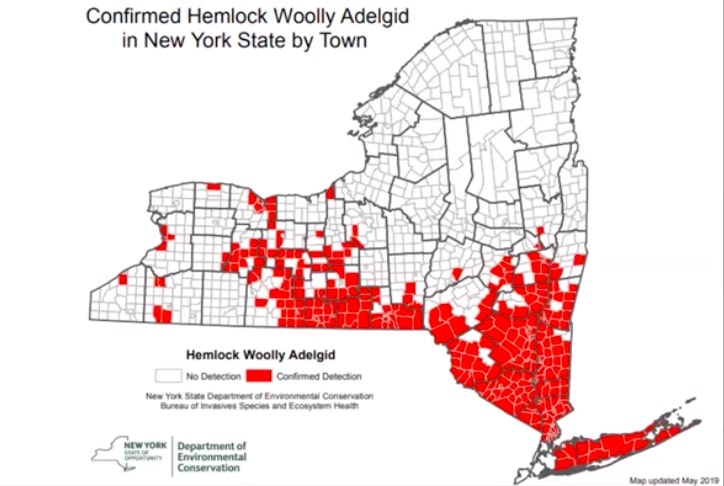

If we lose hemlocks: we lose all the above. Treatment and eradication is possible. Early detection leads to rapid response and good outcomes. For example, a recent eradication of HWA in Warren County in the Adirondacks.

76% of New York’s forested land is privately owned. Land owners can play an outsize role in conservation and management.

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

The Woolly Adelgid is an invasive hemlock pest. Not everywhere, of course. In Asia, for example, it has natural predators that keeps the population in check. In the eastern US, however, it has no predator.

HWA feeds directly from the twig tissue via a long needle-like mouthpart. They literally usurp and block the flow of water and nutrients so that no new growth can occur at the end of the twig.

Look for white, waxy, woolly masses on hemlock twigs, near the base of needles where the adelgids attach to the twig.

It takes 4-20 years to kill a hemlock tree this way — though, with warmer winters, that timeline may be shortened to 4-10 years.

Life Cycle of the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

Complicated life cycle. Two generations of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid per year. First there is a long overwintering generation called the sistens (a wingless parthenogenetic form of a plant louse). Summer/fall/winter, laying eggs in spring. Spring generation, the progrediens (a wingless form of an adelgid bug), is a very short generation, emerges and begins life cycle.

- First generation hatches March/April

- Second generation hatches May/June

Both generations can interbreed. Crawlers, very mobile, spread from April to June. Wool appears in late fall through spring.

Adelgids settle on twigs and don’t move ever again, for the rest of their lives.

Only sistens aestivate (spend a hot or dry period in a prolonged state of dormancy) as nymphs. They wake up in the fall and start producing wool from Nov-June. In April and May they lay their eggs: 50-100 each.

The progrediens lay their eggs at the start of summer. When these second generation eggs hatch they immediately begin feeding — on the new growth at the end of Hemlock branches.

Why So Invasive?

- Adelgids can reproduce asexually — a single adelgid can become an infestation.

- Two generations per year multiplied by 50-100 eggs per adelgid.

- No native HWA predators in the Catskills (no natural population control).

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Management

Treatment prevents the cascade of ecological effects from hemlock loss. Not treating lead to a worse ecological outcome.

Chemical Measures

Two chemicals are used, sometimes in conjunction:

- Imidacloprid is slow-acting (takes a year to knock back populations but can protect trees for up to seven years). Imidacloprid has reduced off-target impacts and low risk to pollinators.

- Dinotefuran is fast-acting (takes three weeks but only lasts one season).

Certified applicators can apply both together but land-owners can only use Imidacloprid.

The downside of both treatments is that each tree needs to be treated individually.

Biological Measures

This is an ongoing long-term research project. Two species are used:

- a beetle from the Pacific Northwest where HWA is native. They only eat HWA and 9,705 have been released so far. Monitoring to see if the populations can reproduce and surivive over season.

- a silver fly also from the northwest and the Canadian Pacific northwest. An abundant HWA predator. The larvae eat HWA eggs. 10,000 released since 2015.

The beetles and flies are currently collected from the northwest and released in New York. Beetles have been confirmed established at five sites in New York.

Research is ongoing into HWA phenology (life-cycle science) to find out when it’s best to release predators, how winter cold affects HWA mortality, to find new biocontrol release sites (including in the Catskills). The project is also using new imaging tech to understand the damage HWA inflicts on hemlock twigs.

How You Can Help

- Know your PRISM / Partnership for Regional Invasive Species Management. For the Catskills, check out CRISP (or APIP for the Adirondacks).

- Landowners: find the hemlock trees on your property and survey for HWA twice per year.

- Treat infestation because the consequence of not treating is a massively negative outcome.

- Community members (landowners, hikers, etc) can survey for HWA and report via NYiMapInvasives. You can also report NO infestation, which is helpful data too.

How to Survey Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

It’s best to survey November though May. Look for branches on ground and for sick/gray hemlock “ghost” trees. Look at the underside of twigs and branches, which is where HWA tends to clump. Check all sides of a tree, and check all branches around the tree you can reach. A lack of new foliage (bright green tips) may mean an infestation.

Final Thoughts

- Winter temps do not knock back HWA. We’ve lost millions of hemlock trees on the east coast already. We cannot rely on Mother Nature.

- Surveys and treatments are critical to keep hemlock in our landscape.

- Biocontrol measures are the future.

More info at nyshemlockinitiative.info, on Facebook and Instagram and you can also email the team directly at NYSHemlockInitiative@cornell.edu.

New York State Hemlock Initiative reports: Great news! NYS Hemlock Initiative staff found one of our HWA predator species at Harriman State Park today! This is wonderful; it means that the beetles we’ve released in previous years were able to establish a population, and will be eating HWA all winter long. Thank you, Laricobius beetles!